Well before I was born, a number of movements sparked worldwide activism and created tangible change. Most were peaceful, some were more direct and some, but not all, achieved their goal. There have been amazing examples of conservation successes across the world, including the campaign against damming the Franklin River in Tasmania and the banning of commercial whaling in the Antarctic region. Today, the more memorable examples of these campaigns are those that mobilized people by using the threat of doing nothing as motivation. Negativity and risk inspired action.

In a time of 24-hour news cycles and daily crises, it becomes incredibly draining to be hit with bad news after bad news. Environment and conservation stories seem to be predicated on impending doom. We hear of another species on the brink of extinction and another piece of habitat lost every day. We become desensitized, as we do to other nightly tragedies. So much so that it becomes difficult to know which calamity to devote our attention to and which to lament. As expected, helplessness follows.

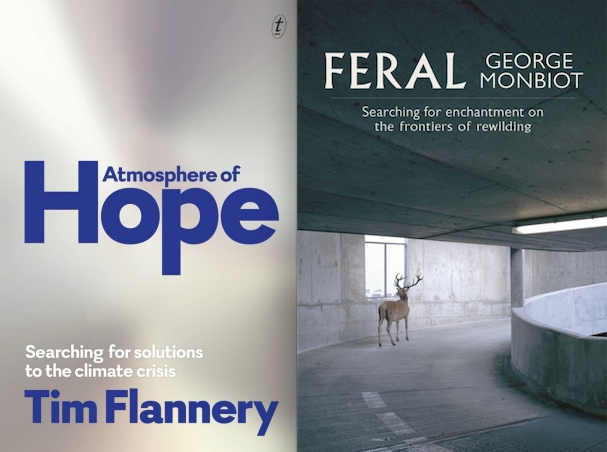

How do we turn this around? First and foremost, we can learn from concurrent debates. If the climate change discourse has taught us anything, it’s that the doom and gloom angle doesn’t work. People don’t engage. We need to apply the same rationale to other realms of conservation and to reimagine discussions in a more uplifting light. George Monbiot did this brilliantly in his book Feral, heralding a new movement of ‘positive environmentalism’. So, in this hypothetical shift towards a more positive outlook, what needs to happen? How do we break the populous free from environmental numbness? Turns out that, in part at least, it’s down to the language we use and the types of stories we choose to tell.

Reading and writing about nature is one of my favourite pastimes. There’s something therapeutic about describing and imagining wild places: a pleasure that goes unmatched. But it’s so hard to remain interested in a succession of stories at the bleak end of the spectrum. Much of the bleakness comes from the way that authors frame their stories: from structure and theme to word choice. It becomes an absolute chore to write – and to read – words like extinction, decline and loss over and over again.

So, why not change the way we talk about conservation? Wonder, awe, beauty, flourish and wild; these words conjure vivid, upbeat images and, as a result, make us inclined to conserve rather than despair.

“Why dwell on a degraded landscape when we can project a vision for its future?”

Bringing hope and optimism to conservation isn’t a new idea. In 2010, James Sheppard and Ronald Swaisgood published a piece in the journal Bioscience lamenting that conservation biology is increasingly ‘a field of despair’. They contended that scientists needed to practice how to be hopeful, so hope could infiltrate through society as a whole. It’s an important notion but, according to Google Scholar, their paper has been cited a mere 24 times. A review published this year in Integrative Zoology by Ruscena Weiderholt highlights the same problem; negativity doesn’t inspire anymore. Consequently, our messages aren’t getting through.

Dorothea Schaffner and colleagues wrote in the Journal of Consumer Marketing this year that negative framing of biodiversity research increases awareness but fails to mobilize action. These days, increasing awareness is only half the job. When the team presented the same research portrayed in a positive light, people were not just made aware but were also inspired to act. It seems a simple tweak of the message really can make a big difference.

But why stop at just tweaking the message? We can also change people’s experience. As a conservation biologist, there are few greater feelings than watching a volunteer’s eyes widen and face light up in ecstasy as they are exposed to a new, thrilling part of nature. Whether it’s a delicate wildflower or the howling of a dingo, the effect is the same – pure wonder and anticipation of what might be waiting around the corner.

It’s this kind of anticipation that the success of the rewilding movement is rooted in; that heightened pulse, those hairs standing up on the back of your neck. People dedicate their lives to chasing these feelings. Experiences not only help find these feelings, but also make them easier to access. As a result, we’re compelled to act, to restore and to conserve. Just so we can get that next hit of feeling wild.

With the constant barrage of sixth extinction and climate stories, our conservation wins risk getting lost in the mire. We need to share our success stories. In the past few months, Australia has focused on the ‘tsunami of violence and death’ that are feral cats (we can thank Australian Environment Minister Greg Hunt for that wonderful turn of phrase). In that time, species like the Western Quoll and Eastern Barred Bandicoot have been reintroduced to their former homes, yet these triumphs seem to have been lost in the white noise of endless news.

In the social media age, one of the best ways to work out which stories most engage people is to track how often posts are shared. Jonah Berger and Katherine Milkman did just this in 2012, suggesting in the Journal of Marketing Research that positive stories go viral more often than those laden with doom and despair. Applying this to conservation naturally means stories of restoration, reintroductions and discovery will engage audiences far better than tales of collapse.

Can this translate into monetary donations? Probably. For the most part, people are careful where they spend their money. Thus, why donate to something that seems doomed anyway? People are more likely to invest in something that is more certain to be successful, creating value for money. The same can apply for conservation projects. Given the choice, I’d be more inclined to donate to the project surrounded in positivity and optimism, rather than another in despair.

Conservation wins get people interested. The wins show it is still possible for humans to work with nature. Sharing and celebrating these good news stories can be powerful tools for inspiring action. They offer a road map, a light at the end of the tunnel, for those feeling overwhelmed by the scale of environmental problems.

That’s not to say that we shouldn’t lose sight of the problem at hand. Or stop communicating it. Scientists are trained to be skeptical – a trait that cannot be, and should not be lost. Maintaining a healthy realism and sticking to evidence is fundamental. Thus, it’s imperative to acknowledge that a myriad of species and ecosystems are in dire trouble but this needn’t translate into pessimism. But that’s only half the job. There are enough people and resources to achieve conservation goals, it’s ‘just’ a matter of mobilising them.

Conservation biologists have a responsibility to communicate facts that increase the awareness of environmental problems. But that isn’t enough. As advocates for conservation it is our responsibility to deliver messages that inspire action. It’s time to return positivity and hope to conservation.

Leave a Reply