I won’t be the last to say it, but it can be easy to forget our eucalypts. Growing up, I took the immense trees that my family were lucky enough to have in our garden and on our nature strip for granted. Some visitors still remark on these overpowering trees, but I never really stopped to admire them until I reached my early 20s, and realised how much nature was a part of who I am. These “eucs” feel like home to me, and it’s often not until we go away and come back that we recognise the significant place they hold in Australian landscapes and our hearts.

Nowadays, I envy those properties with even one beautiful euc standing proudly resolute in the front garden or sentry on the nature strip. I wonder whether the residents admire it each day amongst the hustle and bustle of work, kids, housework; if they understand not just the ecological value of such a plant, but the cultural value of it too. The question that returns to me time and time again as I pass these properties is this: do these people even appreciate our eucs?

Sure, it’s easy for someone like me – a nature lover and now, finally, a self-confessed euc lover – to ask this condescending question. But it’s also easy for me to demonstrate how entrenched these trees are in Australian culture, and that as well as kangaroos, barbeques, beer and red dirt, eucalypts are an archetypal part of the Aussie lifestyle, not just in the physical realm of nature but in the cultural world of books, art and song. So, a better question would be, why wouldn’t people appreciate them?

Without a doubt, the work of Albert Namatjira is a stand-out for art and nature lovers alike. There are really no comparable artworks to Namatjira’s famous depictions of the iconic red, orange and grey-green tones of Central Australian landscapes. The eucalypt often takes pride of place in his pieces, and you’d be hard-pressed to find any other artist capable of portraying the dominant yet naturally cohesive presence of eucalypts in the Australian environment. Leaving behind an extraordinary cultural legacy, his work demonstrates a unique balance between the foreground and background of natural landscapes. Whilst geological features are highlighted in the background, stunning Ghost Gums usually dominate the foreground of his watercolours.

Tragically, the Twin Ghost Gums often depicted in Namatjira’s work were destroyed by fire in 2013, representing both a spiritual and cultural loss for the Western Aranda people. Although these striking eucalypts can still be admired through the incredible lens of Namatjira’s artistic talent, there is unfortunately no bringing back these significant trees. You can view some of Namatjira’s extraordinary work at the National Gallery of Australia.

Another of McCubbin’s most well-known pieces, Lost (1886), arguably achieves the latter, exploring the manner in which eucalypt-clad bush can take hold of a person – especially one not at home in such a merciless environment. Many children have been lost in the bush over the years, and seeing this painting as a child myself, it has stayed with me as an example of how nature can invoke tragedy just as much as it summons relief.

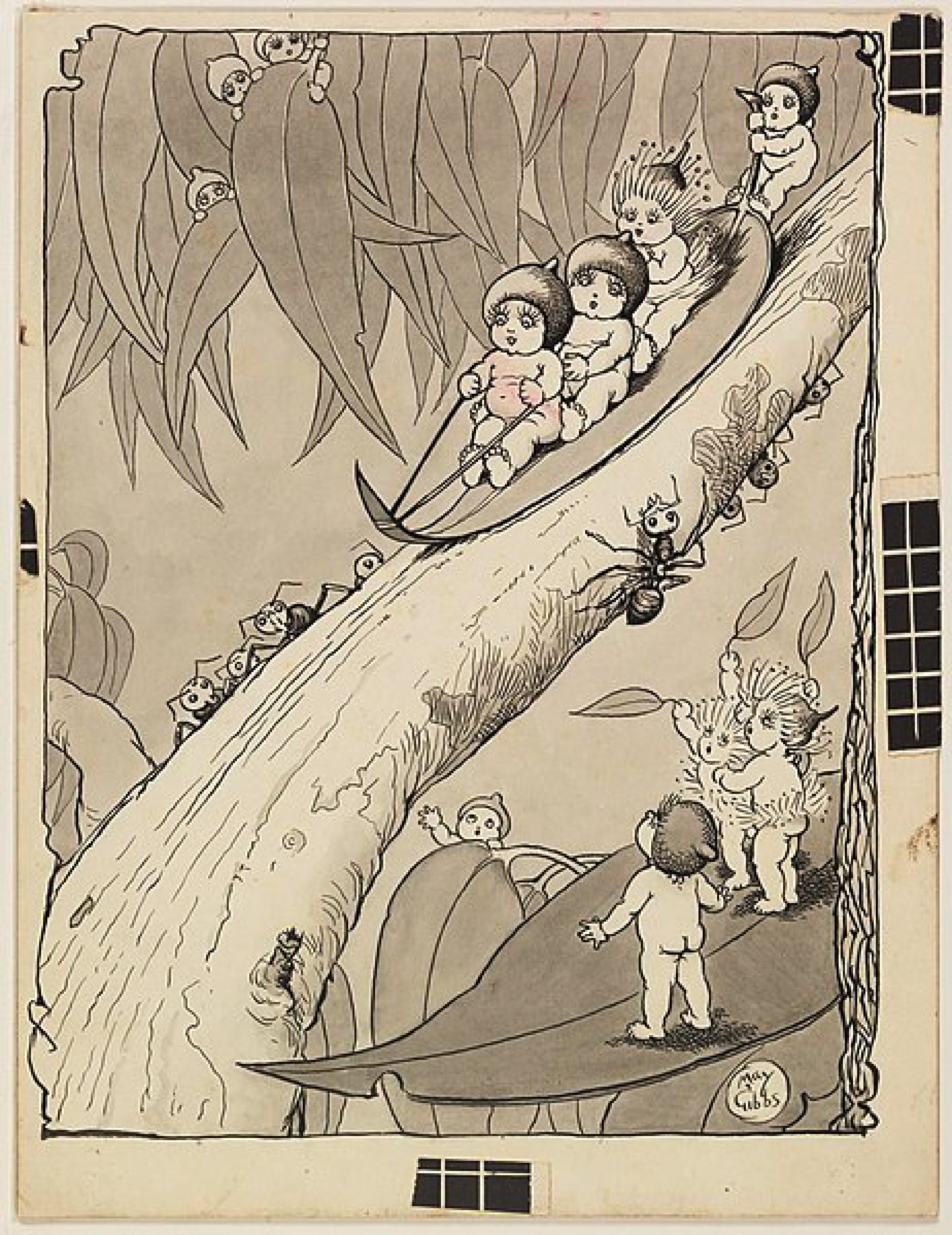

The adventures of these fantastical characters often see them face off with the villainous ‘Banksia Men’, whilst the surrounding scenery is said to be based on the Western Australian bushland where Gibbs played during her childhood. It isn’t difficult to see how influential her work has been within the Australian arts, with both a ballet and musical having been adapted based on her work.

This poem evokes so much in its few lines that is particular to National Eucalypt Day – we celebrate eucalypts so that we might better understand them, and yet there will always be that lingering feeling that although we may appreciate and study them, we will never truly stand in their roots. As someone whose interest in nature grew out of an affinity for animals, it has been, and still is, an interesting journey to now accommodate the lives of plants – in particular, our iconic eucs – into my dialogue with the natural world.

Some may view them simply as vegetation – either an aesthetic element of the landscape or a habitat for animals to utilise – but as shown by words and paint, they are so much more. The question is, where do we draw the line? Will some elements of our eucalypts always remain misunderstood? This, more than anything else, is what I believe makes the admiration of these trees such a transcendent experience – we can know this part of Australian nature both scientifically and culturally, but can we understand it?

Banner image courtesy of MayumiKataoka (Own work) [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)], via Wikimedia Commons.

Leave a Reply