The vast continent of Australia is home to some of the world’s most unusual plants, so it’s hardly surprising that the extinct plants that once dwelt here were just as strange. In fact, Australia was home to some of the earliest plants to colonise land on Earth.

What if we could travel back in time to meet Australia’s first flora and watch it sprout from the silty, primordial mud? Though they may have become extinct hundreds of millions of years ago, the early plants left behind fossils. By carefully reconstructing these lost plants through botanical illustration, we can glimpse the distant past and see how the first plants, and the ecosystems they inhabited, may have looked.

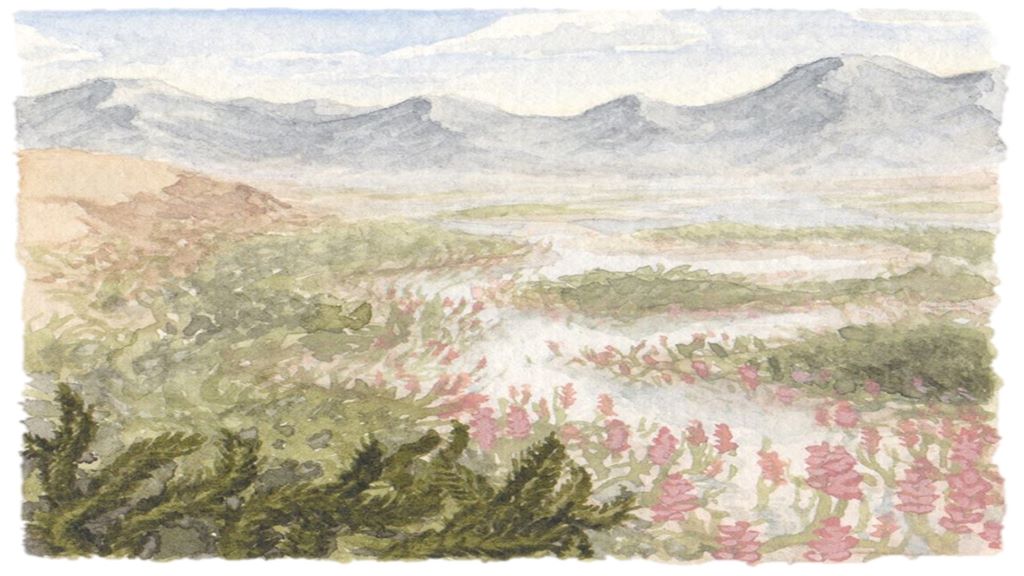

Cast your mind back 420 million years to the end of the Silurian period. The land is barren and almost completely devoid of life; a lonely expanse of parched earth. Deep gullies cut into the mountains and hillsides, a testament to the erosion caused by sporadic rainstorms and a lack of vegetation to keep the earth in place. Below these hills and mountains, vast, shallow, silty rivers transect the lowlands and empty into the primordial sea.

The atmosphere is alien; with only 70% the oxygen content of today, and more than 16 times as much carbon dioxide, it’s a perfect cocktail for the first land plants, but almost certainly deadly for a time-travelling botanist lacking the appropriate breathing equipment.

Below the hills, where a shallow, silty delta meets the sea, the monotonous ochre hues of the earth are interrupted by a lush carpet of green: Australia’s first plants. Though a diverse range of algae thrive in the warm, hospitable oceans, the first land plants have major hurdles to deal with. Not only do they need to keep from drying out, a challenge their marine relatives do not contend with, but they also need to extract enough minerals from the nutrient-poor earth to survive. Unlike the soils of today, which retain moisture well and are rich in organic material, the soils of the late Silurian are almost entirely inorganic and would be deadly for most modern plants.

The early plants overcome these challenges by growing in spots where slow-flowing, sediment-laden water empties into the ocean, creating moist banks of mineral-rich earth, which these early land plants thrive on.

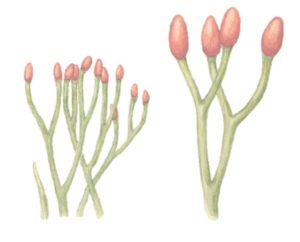

Among the green blanket that covers these silty banks are early plants called Zosterophylls and Rhyniophytina. These diminutive plants have simple branching stems topped with small fruiting bodies called sporangia. Seeds have not yet evolved – they are still millions of years off. Instead, these early plants produce spores. Though neither group survives today, these two are the cousins of the clubmosses, which still occur in small pockets throughout Australia.

Apart from the Zosterophylls and Rhyniophytina, the largest and most complex plant to call Australia’s Silurian coastline home is the ancient clubmoss Baragwanathia longifolia. These stunning plants form bushy thickets which dwarf the tiny Zosterophylls and Rhyniophytina that grew alongside them. This size advantage is thanks to their well-developed vascular system, the most advanced and complex of the time, which allows Baragwanathia to move water and nutrients higher up its stems and, therefore, grow taller than its competitors. Not only does this prevent the plant from getting smothered by its green competitors, but this also permits it to produce its sporangia on taller stems. This helps its spores to catch the wind and spread far and wide along the coastlines of early Australia.

Despite the availability of water and nutrients, life at the mouth of a Silurian estuary is precarious at the best of times. With every flood or storm, silty banks and their green inhabitants are washed away and buried. While this is the end for some unfortunate plants, it also facilitates their fossilisation. It’s thanks to this turbid environment, and the ideal fossilisation conditions it provided, that we have a treasure trove of fossils from this period.

While some silty banks are washed away, other new banks are formed on which spores can land and begin new colonies of plants. This chaotic environment may seem like a harsh habitat for our early plants, but it’s this pressure to survive that will help drive them to evolve and diversify into the increasingly complex forms that cover the earth in green today.

Though Australia’s first plants may be long gone, their descendents live on as Australia’s modern flora. The plants we see around us today are a testament to the ability of their ancestors to adapt and thrive in ancient Australia’s harsh conditions. Our continent’s first plant inhabitants may be gone, but they need not be forgotten.

Banner image is an original illustration by Cameron Brideoake.

Cameron Brideoake is a natural history illustrator based in Melbourne. Inspired by the great naturalists of old, he works in traditional media painting his subjects in watercolour and gouache. A fanatic for everything Earth science related, Cameron’s special interests include paleobotany, entomology and conservation. To follow his latest projects find him on Instagram or on Facebook.

Leave a Reply