Amid the battle to save our increasing list of threatened and endangered species it is important to remember the ones already lost to history. Threatened Species Day commemorates the date on which the last known Tasmanian Tiger died in Hobart Zoo in 1936. Though numbers had been in rapid decline for decades, it was not until this same year that the species was added to the protected wildlife list.

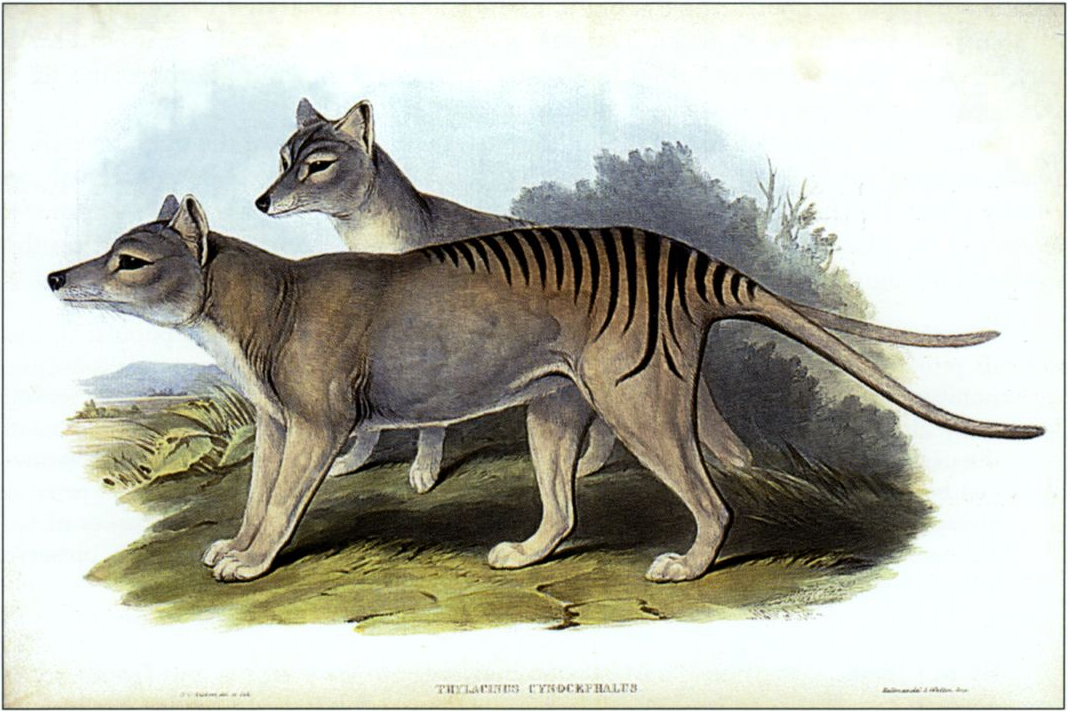

The Thylacine, despite its dog-like appearance, was a carnivorous marsupial most closely related to the Numbat and the Tasmanian Devil. Though Thylacines used to roam Australia’s mainland and New Guinea, those populations became extinct roughly 3,000 years ago – around the time the Dingo was introduced – although it’s suggested numbers were already decreasing even without the Dingo’s help.

The Tasmanian Thylacines, however, continued to survive until the pressure of habitat loss took their toll at the same time as the animals were ferociously hunted by humans, who believed they posed a danger to livestock. After the species was hunted to extinction in the wild, the remaining few individuals failed to thrive in captivity.

The research has revealed that the Thylacine species had low genetic diversity prior to its extinction, similar to the problem faced today by the Tasmanian Devil. Significantly, Pask’s paper also emphasises the striking incidence of convergent evolution that has occurred between the Thylacine and its very distant canine relatives. Pask is hopeful that the information provided by the research into the Thylacine’s genome can aid in the fight against extinction for other species.

As for the Thylacine, could it ever be seen walking the earth again? Although theories persist about the animal’s continued presence prowling secretly through the thick Tasmanian forests, and no shortage of avid wildlife enthusiasts continue to trek through the wilderness in search of a hidden individual, there’s no evidence to suggest that any of the creatures remain. It’s not impossible, says Pask, but unlikely. ‘You have no idea how many zip-lock bags of poo have been mailed to me in the course of this project,’ he said in a recent talk on his work at the Royal Society of Victoria. ‘None of them has been genuine so far, but keep sending them, I’ll keep checking them,’ he laughed.

In his talk, Pask discussed the idea of resurrecting the Thylacine – a feat made theoretically possible by the mapping of its genetic information. ‘We’re a long way off being able to do it,’ he said, but nevertheless he believes that, if possible, it would be the right thing to do to bring back this species, whose downfall was brought about by the intervention of humans.

Allaying concerns over a Jurassic Park–style disaster, he explained that, unlike the dinosaurs, the Thylacine is recently extinct (within the last hundred years counting as recent in biological terms) and the habitat in which it once lived still exists, largely unchanged. Therefore, the chances of unforeseen negative consequences would be small. Rather, bringing back the Thylacine could reintroduce an important apex predator into the Tasmanian ecosystem and restore some balance which has been lacking since the Thylacine’s demise.

The process of de-extinction, Pask explained, is not the same as cloning. To resurrect the Thylacine would require a close genetic relative to host the embryo, into which the genetic changes would be engineered. The host animal, most likely a Numbat, would give birth to a joey that was not quite a true Thylacine, but more of a Thylacine-Numbat hybrid. However, this could possibly serve as a useful way of increasing the genetic diversity of the Thylacine, making it more resilient as a species than it was when it was last alive.

Apart from the scientific practicability of resurrecting the Thylacine, if such a thing did become possible in the future, a de-extinction project might have to be weighed up against the benefits of using available funds and resources to invest in the survival of other species that have not yet suffered the Thylacine’s fate. In keeping with the adage ‘prevention is better than cure’, it’s clear that it’s far easier to save a species from extinction than to raise it from the dead. Additionally, it is important to note the role that popular science media plays in spreading this idea of de-extinction. In the case of Pask’s paper, there were unfortunately some significant miscommunications made by the media when it came to publicising the research.

The Thylacine remains the poster-animal for extinction in Australia, but while a select few animals such as the Leadbeater’s Possum and the Orange-bellied Parrot command much of the public attention, Threatened Species Day is a good time to remember that most of us have probably never heard of the majority of species on our nation’s critically endangered list. Mammals such as the Christmas Island Pipistrelle, reptiles like the Leaf-scaled Sea Snake and birds like the Plains-Wanderer, as well as a long list of little-known fish and arthropods, are in danger of falling out of existence without ever entering the public consciousness. The more we do to educate ourselves about our threatened flora and fauna, the better chance we have of saving them before it’s too late.

Banner image courtesy of Baker; E.J. Keller. [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons.

Leave a Reply