Our psyche, our health, our evolution is informed by the state of the natural realm. Philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty believed that it is through nature that human beings can tap into the ‘deep world of untamed perception’ that exists on the periphery of our existence; through the chaotic, omnipresent, and often uncontrollable natural world can we better understand not only ourselves, but the diverse range of ‘others’ that exist around us. Human beings evolved from the natural, the untameable, the wild – but our treatment of the non-humans with which we share our home suggests that we’re in denial of our own prehistory.

According to the Australian Museum, biodiversity is defined as ‘the variety of all living things; the different plants, animals and micro organisms, the genetic information they contain and the ecosystems they form.’ This, many would agree, is a broad definition, and one that makes it difficult to ascertain exactly how important biodiversity is in different contexts and why it is that we must value it – not just in a biological sense, but a philosophical one too. After all, aren’t we also a part of this biodiversity? Without it, would the human species exist at all? And, as I’ve just done, why do we constantly need to remind people of their own self-worth within nature to make them protect it? Isn’t the wonder of nature itself enough? Can science answer these (seemingly endless) questions?

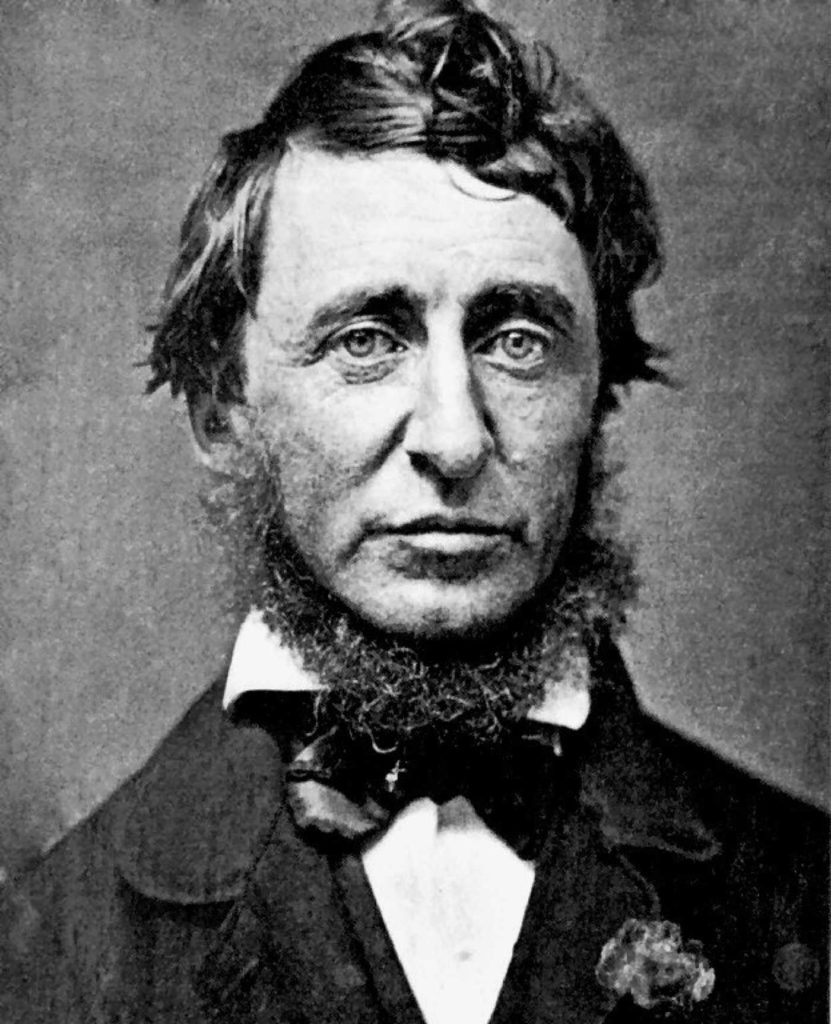

Although science is the bread and butter of our understanding of ecosystems, it is not our only option for interpreting the profound and ambiguous puzzle that is biodiversity. It is an interesting – and important – exercise to explore the realm of ecophilosophy as well. Ecophilosophy, or environmental philosophy, refers to the study of quite literally what the word refers to: the combination of ecology with philosophy, allowing us to better understand the relationship between our natural environment and what it means to be human. It is a term primarily penned by academics, but is fast becoming a common way to describe the teachings of well-known naturalists and environmentalists, such as Henry David Thoreau, Rachel Carson and Aldo Leopold.

However, it is a school of thought that is often misrepresented. Just as scientific theories can be over-simplified, confused and manipulated in the public sphere, so too can ecophilosophy. It is perhaps time for it to be brought to the forefront of environmental discussions that are not simply being had by academics, but by the general public as well. So what is ecophilosophy? And why should you care about it?

To begin with, ecophilosophy explores not just the human but the non-human as well – that is, the animals, plants, bacteria, landscapes that together form the physical world of nature – and the difficulty that we have in separating our own lives from the lives of the non-humans who cannot speak for themselves. But let’s start simple, by looking at the human.

Humankind’s long history of disregard and exploitation of nature’s diversity can be likened to our just-as-long history of disregard and exploitation of human diversity. Many ecophilosophers question whether problems accepting social diversity, in regards to race, class and gender, are in fact related to the same problems we’re facing in the biodiversity sphere. Some believe that making progress in, say, the fight for gender equality, could also lead to an increased appreciation for the natural world.

But just how might such an extension of our morality occur? To understand this, we must first understand the thickly wooded forest that is ecophilosophy. Firstly, there are different branches to consider. Ecofeminists, for example, support the idea that overcoming the various patriarchal elements ingrained in modern society could result in a less anthropocentric understanding of nature. Ecocentrism is instead what ecofeminism and other schools of ecophilosophy aim for – that is, a world in which humans share a more equal standing with other organisms and elements of nature.

Ecofeminists believe that increased gender and racial diversity, and the acceptance of such in workplaces, popular culture, and everyday life are vital aspects of the shift towards ecocentrism. Their philosophy does not dictate that men are solely responsible for global warming, the felling of forests or the disappearance of the dodo, but rather contends that the patriarchy fosters a toxic society of dominance, control and greed that has led to many modern ecological concerns. Not only would gender equality benefit humans, but it could also lead to a broader, more diverse perspective of the non-human lives that are currently so undervalued.

Comparatively, deep ecologists present the broader philosophy of treating all elements of the natural world as inherently valuable, no matter what worth they may have in human circles. This is an idea that is very much at odds with the concept of ‘environmental accounting’ as a proposed solution to the biodiversity crisis – deep ecologists do not believe in prioritising the conservation of one organism over another based on human gain. As ecofeminism was born out of deep ecology, this is an understanding shared by both groups, and raises the issue of how we can better protect non-human species and natural places when many humans rely on them for their livelihoods.

As many in the industries of science tend to value firm facts and tangible outcomes, it can be difficult for some to wrap their heads around the extremely theory-based study that is ecophilosophy. However, it is also vital for such people to remember that whilst science is the bread and butter of ecology, philosophy was once the bread and butter of science. That is not to say that the two don’t have their differences, or that one is more significant than the other. But in a world where money talks and arts degrees walk, it is more important than ever for people from both sides of the arts-science spectrum to consider the role of ecophilosophy in stimulating discussion of the moral and often non-tangible concepts of biodiversity.

For example, should we value the existence of a particular species over another if we can only afford to save one? Does human life always come before the non-human? Would it ever be ethical to more strictly control human population growth to stimulate biodiversity? Although there are some black-and-white ecological answers to these questions, philosophical explorations can result in new understandings and appreciations that are vitally different to those of science.

Ecocriticism – the study of literature and the environment – could be viewed as an offshoot of the ecophilosophy discipline. Its existence amidst the development of literary genres such as ‘clifi’ (climate fiction), eco-fiction, and ecopoetry suggests a strong move towards issues of environmental catastrophe in writing and popular culture. Novels such as The Windup Girl (2009), Oryx and Crake (2003), Clade (2015) and even The Road (2006) alongside films such as Interstellar (2014) and Snowpiercer (2013) demonstrate this – but there need to be more. Whilst science is the best way to discover solutions to the modern environmental crisis, the arts can help us imagine a terrifying future in which humans have chosen not to act on science.

Although ecophilosophy is not without its problems, it presents another way for humans to better comprehend the vast array of societal, scientific and ecological issues that exist in connection to biodiversity and ecocatastrophe. The arts and sciences are linked in countless ways, and we have come to a time in human (and non-human) history where, more than ever, each requires the other in order to enhance our understanding of the natural world on which we so depend. So let’s delve into this realm of untamed perception, and immerse ourselves in the parts of nature that challenge our idea of what it means to be human.

Banner image courtesy of Chris McCormack.

Leave a Reply