As a diver and dive guide, I have always felt a bit awkward searching for the small, hidden things at the bottom of the ocean rather than looking for bigger, faster, more obvious fishes, mammals and other creatures. I guess I have always found the search rewarding. I have felt pride in finding creatures other divers would have overlooked. During the very first dive I embarked on as a kid, I saw a sea slug, or nudibranch as scientists call them, and I was hooked. I have dived in many a tropical location since, with plenty of big and magnificent animals, but my eyes always end up looking for these flashy gems. And as it turns out, I am not alone…

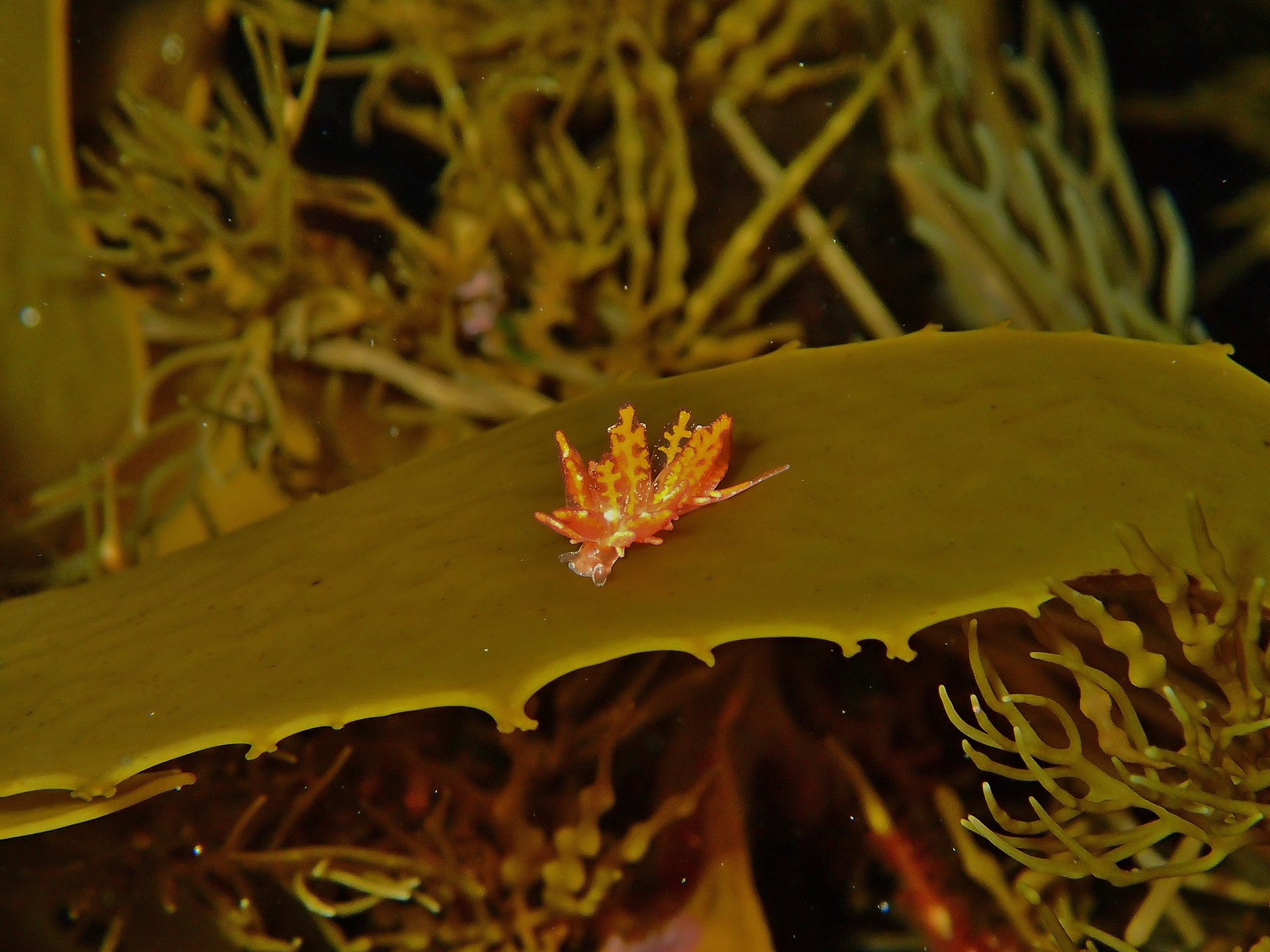

First, though, let me tell you more about these amazing creatures. Nudibranchs are a diverse group of marine molluscs that are found around the globe from Antarctica to the tropics at all sorts of depths. With the gills they wear on their backs that give them their name (nudibranch means ‘naked gills’), the retractable sensory tentacles that allow them to navigate and their vibrant colours, some of them look like aliens from another planet.

Not only do they exhibit a variety of shapes, sizes, patterns and colours, but they also possess amazing adaptations to cope with their environment. Some of them might look fragile and vulnerable, but don’t feel sorry for them. They can actually turn compounds from their food sources into chemical defences to protect themselves, taking the concept of ‘You are what you eat’ just one step further. It works so well that they don’t need a shell when they are adults, unlike some other molluscs.

Using chemicals from their food to their advantage also gives some species the ability to become solar-powered, just like plants. And if you’re not yet convinced that these animals are amazing, wait until you hear about their quirky reproductive strategies. Not only are they hermaphrodites, but some species have a detachable penis that is left inside their mate to block out the sperm of competing males, and that can grow back within a day for copulation and ensure the offspring are theirs.

This year in April, divers, snorkelers and beach goers joined forces to gather data on the overlooked yet beautiful sea slugs of Port Phillip and Western Port Bays for the first time, following in the footsteps of groups throughout Australia who have conducted sea slug censuses since 2013.

As a sea slug nerd myself, I wanted to know more about this citizen science project organised by the Victorian National Parks Association (VNPA), and so I sat down with Kade Mills, ReefWatch coordinator, to understand how the process all began and what exciting results emerged from the first survey. I chatted with Bob Burn, builder by trade turned sea slug expert, to discuss some of the results of the census and to get a feel for how unique Victoria was in terms of sea slugs. I also interviewed Professor Steve Smith from Southern Cross University, NSW, co-founder of the Sea Slug Census program, to learn more about the surveys throughout the country.

Kade remembers seeing posts on Facebook about the sea slug censuses in Nelson Bay, NSW and thinking that the surveys were ‘such an awesome idea’. It got him ‘thinking about how many sea slugs there are in and around Port Phillip Bay and Western Port’; with the many passionate divers and underwater photographers in the area, he thought that the survey would appeal to Victorians as well and got in touch with Steve to discuss how to get things started. For Kade, it was a no-brainer. The fact that these creatures are so flamboyant, easy to photograph and a good indicator of climate change would surely rally the troops and make the sea slug census an event the Victorian community could really connect with. Not only do divers and snorkelers have a keenness for sea slugs, but the surveys also allow people that aren’t divers and snorkelers to participate by simply exploring local rockpools. Altogether, 150 citizen scientists happily braved the chilly weather to join the hunt and rose to the challenge of spotting as many nudis, as they are affectionately called, as possible. Steve describes the participation as ‘absolutely phenomenal’ and the biggest in Australia so far.

Contributors were asked to find sea slugs, photograph them and send the photos via email for identification, with the depth and location of sightings. In total, 40 teams sent images of 53 species of sea slugs from 21 different locations in and around Port Phillip Bay and Western Port. As this was the first survey in the area, the aim was to establish a baseline. As Kade explains, ‘We know these species are around; they have been found before, Bob [Burn] has described them, but now we’ve got a baseline for when we do this again in following years.’ The true value of the sea slug census, he explains, ‘is going to come after multiple years of doing it’. Thanks to the census, we will be able to determine whether the same species are around at the same time of year, and whether there are seasonal differences in sea slug distribution. Already, citizen scientists have sighted a species that is new to science and doesn’t have a name. Bob, the author of a ‘little slug book’ as he modestly calls it, thinks that ‘the census should be encouraged’ and adds that in the future, training would be extremely valuable to ensure divers know what they are looking at, especially when photographing the sea slugs they encounter so they can include features that will assist in their identification.

According to Bob, Victoria has ‘an excellent diversity’ when it comes to sea slugs with over 400 species found in the state’s waters, although not all of them have been formerly described. What is special about Victoria, he explains, is that while there are species that are there some or most of the time, we also get ‘incursions coming down the East Coast, from the tropics and the temperate waters of Southern Queensland, and northern New South Wales.’ At times, ‘those currents bring tropical or tropical-looking species’ into the eastern parts of Victoria. Weaker currents along the southern coastline of the continent occasionally bring Western and South Australian species into western Victorian waters as well. Even though most species are less than 10mm long, Bob points out that Victoria has some ‘very interesting species, which seem to have been here for millions of years because there are fossil records of similar things dating back as far as the middle Miocene [23 million to 5.3 million years ago] in other places’.

Steve explains to me that the sea slug censuses started as ‘friendly rivalry’ with his postgraduate student, Tom Davis, in Nelson Bay. They ‘wanted to see who could count and photograph the most species of sea slugs while […] diving.’ Then they decided that other people might enjoy the challenge and launched a census in 2013, which they thought at first would be a one-off event. Five years later, the censuses are not only still going strong, but they have expanded to other locations in Australia and overseas and are providing some amazing results, including the documentation of species expansions linked with climate change.

Steve explains that the reason the sea slug censuses are so successful is that participants learn through the process. Thanks to the report generated for each one, they get to see what they have missed and learn a bit more about sea slugs. He also points out that the citizen science program is a ‘fantastic tool for filling in gaps about the distribution of sea slugs, and for longer-term monitoring of how distribution patterns change.’ Beyond that, Steve sees the censuses as ‘a vehicle for trying to foster support for conservation of our marine habitats.’

So where can you look for these creatures? Bob and Steve recommend looking in dark places, as you tend to find them under algal fronds and ledges, out of the way. Some sea slugs feed on hydroids (small animals related to jellyfishes), so this is another good place to look, as well as where there is not a lot of wave action and at very low tide in rock pools. Their last bit of advice was to stay still and look for movement, so just slow down and focus on a small area instead of trying to cover a large area.

For Kade, the benefit of the sea slug census exceeded just collecting data on sea slugs, as people were seeing other creatures, including crabs, small amphipods and isopods, ‘almost as a by-product of looking so closely’. ‘They just paid more attention to what was down there’, he points out. While there is currently funding available for three years in Melbourne, Kade is hoping the sea slug census will continue in an ongoing manner and will continue to challenge and amaze Victorians in the long-term, mirroring the success of the Great Victorian Fish Count. Surely, it will; as Kade points out ‘there’s a real underwater network of nudi nerds out there’.

Whether you’re already converted or don’t know anything about sea slugs yet, make sure you join the fun this October. The Melbourne Sea Slug Census will be back from October 12th-15th. Let’s see if we can beat April’s numbers of citizen scientists in the water.

Banner image of the nudibranch Tenellia sibogae eating hydroids in Nelson Bay courtesy of Steve Smith.

Leave a Reply