“The truth is that Antarctica has little time for humans….. This is the only continent on Earth where people have never lived. And until very recently in human history it was as mysterious to us as the Moon.” – Gabrielle Walker

I sat on the snow-covered ground waiting for sunset with another solo female traveller and one of our guides. It was a few days before Christmas and we were part of a small group from our expedition vessel camping overnight on an island surrounded by glaciers. The sun never sets during the Antarctic summer and nighttime skies darken to shades of twilight only in the early hours of the morning. We passed the time entertained by several chinstrap penguins clumsily and determinedly trying to join others on a rock just offshore. Every so often we would hear the bone-chilling, thunderous crash of ice calving that signalled a final moment in its 14,000-year journey back to the ocean or in this case, the dark blue waters of the Antarctic Peninsula.

Finally, just after midnight, the sky began casting shades of pink and gold across the ridges of ice rising out of the Bellingshausen Sea a few kilometres across from our island perch. It was definitely worth the wait.

The Austral summer is the only tourism season in Antarctica. Depending on conditions, ships can make the voyage south from October to April, but once the 15 million square kilometres of winter sea ice encircles Antarctica’s landmass, the continent becomes inaccessible by sea一even for the most indestructible icebreakers.

Like most of the nearly 52,000 tourists in the 2017/2018 season, I left for Antarctica from Ushuaia, Argentina. With a hodgepodge of roughly 114 ice-eager passengers and 70 crew, our 92-metre Russian icebreaker-turned-expedition vessel cruised out of the Beagle Channel and south across the Drake Passage towards the White Continent. There, we would spend five days exploring the Antarctic Peninsula, which played an important role in creating the frozen landscape we had come from all over the world to see.

Vessels must have 400 or fewer passengers in order to anchor and shuttle tourists to Antarctica and its islands (large cruise ships still venture south, but they must remain at sea). In addition to educational lectures whilst at sea, small-to-medium-sized expedition vessels provide passengers with zodiac cruises around coastal inlets and icebergs as well as land excursions to scientific bases and penguin colonies. Many also offer add-on adventure activities, such as kayaking or scuba diving. I was one of 16 pre-registered sea kayakers on my vessel. Several briefings and a reasonable level of fitness were required before we were given our paddles and full-body drysuits. Kayaking in Antarctic waters is no paddle down the Yarra — we had to be ready at any moment to navigate the aftermath of a somersaulting iceberg or calving glacier that could send metre-high waves of frigid water barreling towards us. Luckily, that never happened on my trip, but we always kept our distance from icebergs and the shorelines just in case.

Kayaking in polar waters was one of the most serene, humbling experiences I had in Antarctica. On one day we followed minke whales around a bay. From a distance, our guide explained that whales often come into the Peninsula’s glacier-lined bays to scratch themselves on the rocks and ice below the surface. Another day, we spent five minutes without a camera, our paddles or our voices to break the piercing silence in the back of a long inlet. No Russian icebreaker in sight, I was completely present in the enormity of the vast, frozen wilderness towering around me. I felt small and irrelevant in the kayak, but I also felt incredibly calm and peaceful. I still get chills when I think about how I felt at that moment.

The waters between Antarctica and South America, where the Pacific, Atlantic and Southern Oceans meet, are some of the most turbulent in the world. They are known to shake and rattle, with ease, the inconsequential humans who cross them. Crossing the Drake Passage on our return to Ushuaia, it was clear that the “Angry Drake” was upon us. For hours, the oceans sent our vessel hurling over 10-metre waves. I almost regretted befriending the ship’s Safety Officer and the ensuing knowledge that even he was nervous about the conditions, that one of our stabilisers was not working properly (most likely from striking a whale) and that it was one of the worst crossings of his season.

I spent the last night of my Antarctic adventure wide awake in my cabin on the lowest passenger deck of a tumbling icebreaker with my porthole covered and locked for safety. I felt as though the continent was booting us back to where we came from with a warning not to return and I wondered if I should have ever travelled to Antarctica in the first place.

Then I thought the same thing again, more seriously— should tourists, or anyone else for that matter, travel to Antarctica?

In just two seasons after my trip, visitors to Antarctica increased 43 per cent with a staggering 74,400 tourists finding their way to the Seventh Continent between October 2019 to April 2020. While visitation numbers are low compared to many other destinations, extreme environments and multinational political agendas make tourism challenging to monitor and regulate in Antarctica.

International regulation of Antarctica began in 1961 when 12 countries signed the Antarctic Treaty. Now signed by more than 50 nations, the Treaty “established that the region south of 60°S latitude remain politically neutral; no nation or group of people can claim any part of the Antarctic as territory; countries cannot use the region for military purposes or to dispose of radioactive waste; and research can only be done for peaceful purposes.”

Many documents have been added to the original Treaty’s stipulations over the years, but it was another 30 years before tourism began to be regulated in the region. The Madrid Protocol, signed in 1991 to better protect the pristine environment and wildlife, not only banned all mining but also required environmental impact assessments of all human activities in Antarctica.

In response to the Madrid Protocol, seven tour operators formed the International Association of Antarctic Tour Operators (IAATO), an industry alliance to promote and enable safer and more sustainable private-sector travel to Antarctica. Together with Parties of the Antarctic Treaty, IAATO develops guidelines for preserving wilderness, protecting wildlife, respecting scientific research and setting safety, landing and transport standards. Whether travelling on a charter yacht, a deep-field air tour to the South Pole or an expedition cruise around the Peninsula, all private and individual operators must adequately follow and disclose their protocols and impacts in order to achieve and maintain IAATO membership and accreditation.

However, no formal policing exists in Antarctica, so operators must self-regulate. Self-regulation requires a level of trust that operators will be honest and transparent in their assessments. Challenges to tourism regulation also stem from an increasingly diverse tourism portfolio that makes proactive standards-setting difficult. Additionally, the limited number of long-term, centralised studies on human impacts in Antarctica only exacerbate regulatory challenges in Antarctica.

Some regulations and standards have been effective in reducing our footprint in Antarctica, such as limiting numbers of visitors who can land at a time, setting strict restrictions on approaching wildlife, mandating vacuuming of clothes that may carry invasive species and taxing waste dumping or single-use plastic. Travellers themselves also play a massive role in creating a more sustainable tourism industry by choosing to travel with sustainable operators or offsetting the carbon emissions from their long-haul flights. As much as travellers can reduce their impacts before and during a holiday, what they can do after is perhaps just as important一they can talk. And for a continent with no indigenous population, tourists can provide a voice that goes a long way.

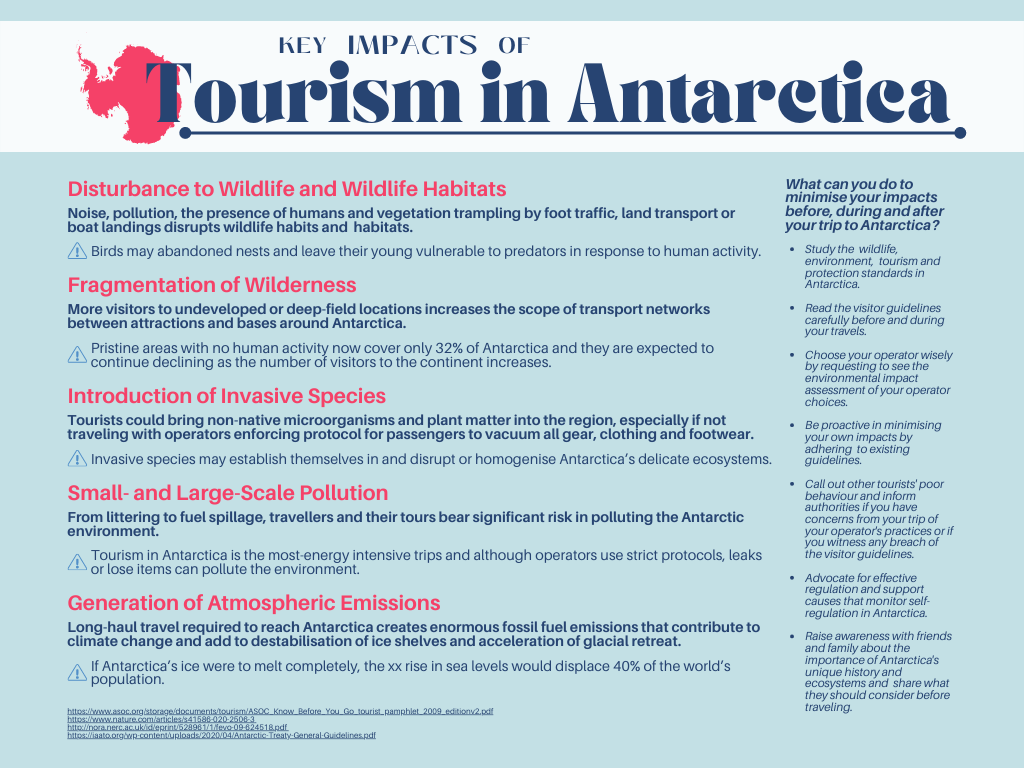

All human activities impact the natural environment of Antarctica, but leisure activities have much less potential to benefit Antarctica than those related to science and scientific discovery. The infographic below describes tourism’s key impacts and explains their repercussions as well as what travellers can do to minimise them.

So, should tourists travel to Antarctica? I think that comes down to you, the tourist. Will you be a voice for the continent when you return? Or do you just want a cool puffy jacket to wear once a winter? Perhaps you’re on the edge, debating if a trip to the ice might inspire your inner scientist, waiting all winter in Tassie for summer when RSV Nuyina finally takes you back to Mawson Station where you spend your days deciphering climate change indicators from ice chunks older than Egypt’s Pyramids.

Whether you journey to Antarctica or not, I encourage you to immerse yourself in learning about and become an ambassador for the Antarctic ecosystems and natural resources that undoubtedly determine our future. I encourage you to advocate for the safekeeping of the scientific haven that nurtures peaceful knowledge-sharing from the bottom of the world. I encourage you to study the rich histories of the Frozen Continent. You might discover a climatic history of naturally occurring, carbon-induced climate change taking place at a much slower rate than that of our climate today, a natural history teaming with evolution phenomena or a human history of a place bloodied by a gruesome whaling industry. A place that for so long was only explored and exhibited by a few martyrly intrepid men and a place protected by an unlikely Treaty that remains an overlooked, almost forgotten feat of Cold War diplomacy.

Antarctica clings to those who go. Its walls of ice make brutally clear the myriad of harrowing scenarios sure to follow in their wake as they continue to melt. Its hostile conditions elicit a daunting realisation of the vulnerability of our existence in a land humans have never permanently inhabited. Its uncanny juxtaposition of unfathomable immensity and inescapable fragility unintentionally intrigues its onlookers to watch as the earth’s last great wilderness around them becomes irreversibly unwild.

But those who bear witness to Antarctica’s transcending resplendence must not be idle. We bear a responsibility to arouse consciousness in our distant homelands and their tethered spirits that the fate of Antarctica, once protected by the currents of the southern oceans, now lies in our hands.

Ways to experience Antarctica without actually going

- Visit a gateway city (we’re lucky we have one in our backyard!)

- Visit Antarctic exhibits in Australia

- Islands to Ice exhibit at Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery

- Antarctic Journey exhibit at Phillip Island Nature Parks’ Nobbies Centre

- Dive into digital content

- Keep up with the Australian Antarctic Division

- Experience their interactive Ice Nomads content

- Watch their Breaking the Ice video series

- Listen to their podcast: AusAntarctic

- Subscribe to their Antarctic Insider newsletter

- Read their Australian Antarctic Magazine

- Follow their socials

-

Sublime Antarctica. Photo by Olivia Salsbery.

Leave a Reply